Modeling Driver Behavior with Cognitive Architecture

- Salvucci, Dario D. “Modeling driver behavior in a cognitive architecture.” Human factors 48.2 (2006): 362-380.

Intro

This paper explores the development of a rigorous computational model of driver behavior in a cognitive architecture – a computational framework with underlying psychological theories that incorporate basic properties and limitations of the human system

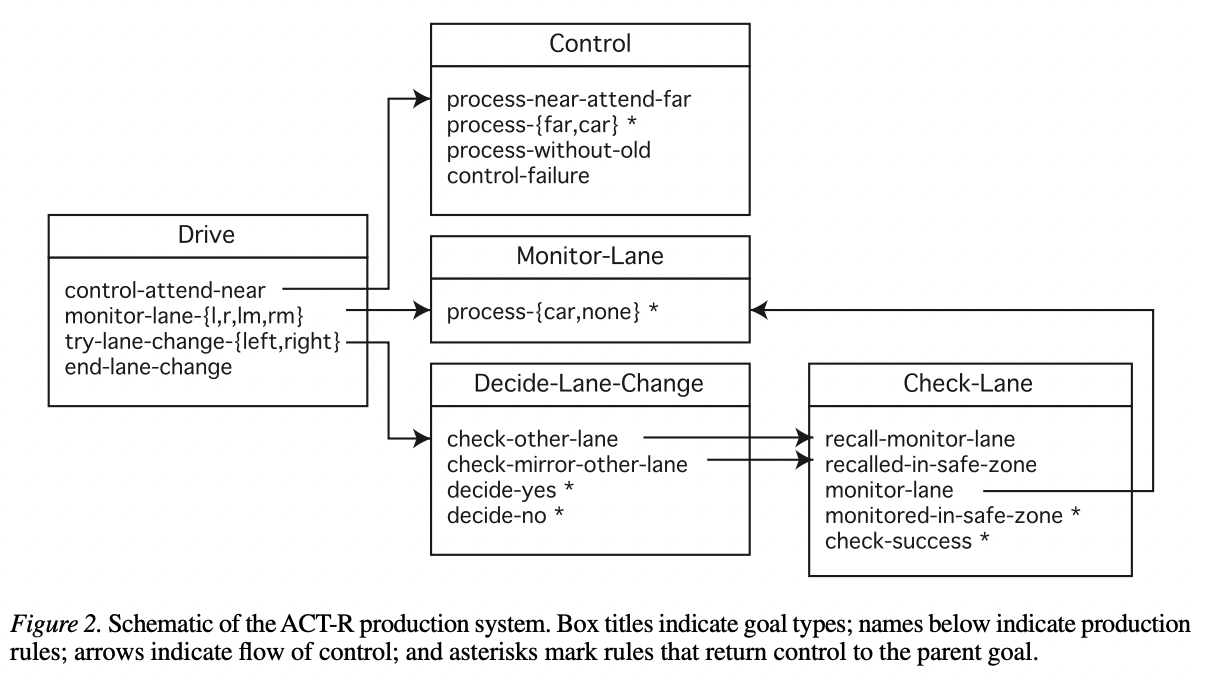

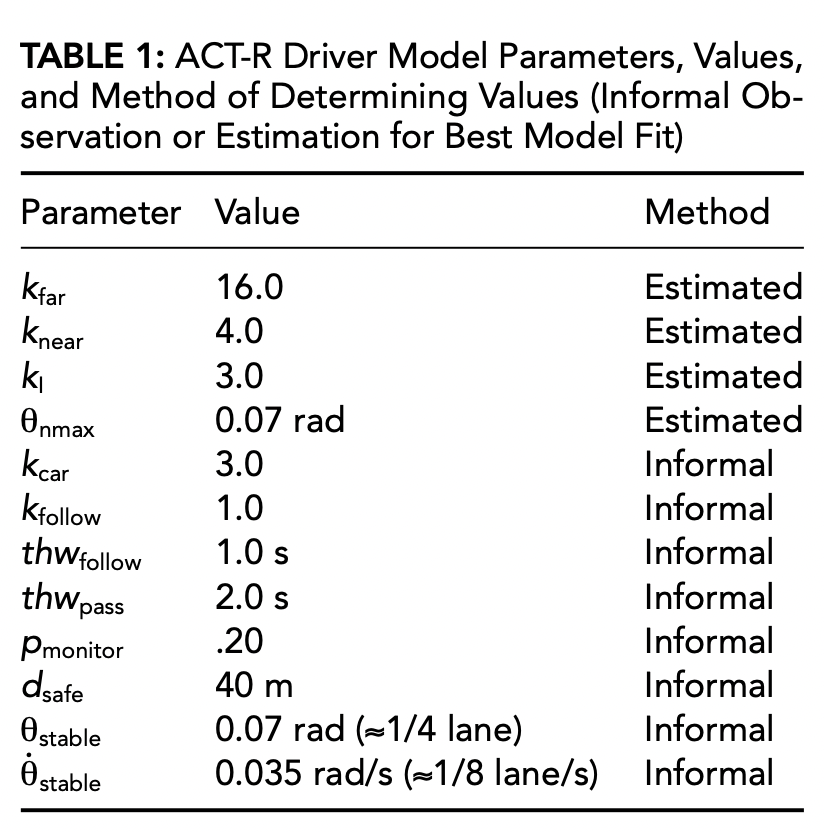

An integrated driver model developed in the ACT-R (Adaptive Control of Thought-Rational) cognitive architecture is described that focuses on the component processes of control, monitoring, and decision making in a multilane highway environment

This model accounts for the steering profiles, lateral position profiles, and gaze distributions of human drivers during lane keeping, curve negotiation, and lane changing.

The model demonstrates how cognitive architectures facilitate understanding of driver behavior in the context of general human abilities and constraints and how the driving domain benefits cognitive architectures by pushing model development toward more complex, realistic tasks

Driving and Integrated Driver Modeling

useful to view driving and driver modeling in the context of the embodied cognition, task, and artifact (ETA) framework (Byrne, 2001; Gray, 2000; Gray & Boehm-Davis, 2000).

As the name suggests, this framework emphasizes three components of an integrated modeling effort: the task that a person attempts to perform, the artifact

by which the person performs the task, and the embodied cognition by which the person perceives, thinks, and acts in the world through the artifact

A sound understanding of each component is critical to developing rigorous integrated models of driver behavior.

Michon (1985) identified three classes of task processes for driving: operational processes that involve manipulating control inputs for stable driving, tactical processes that govern safe interactions with the environment and other vehicles, and strategic processes for higher level reasoning and planning

Some tasks are not continual but intermittent, arising in specific situations – for instance, parking a vehicle at a final destination.

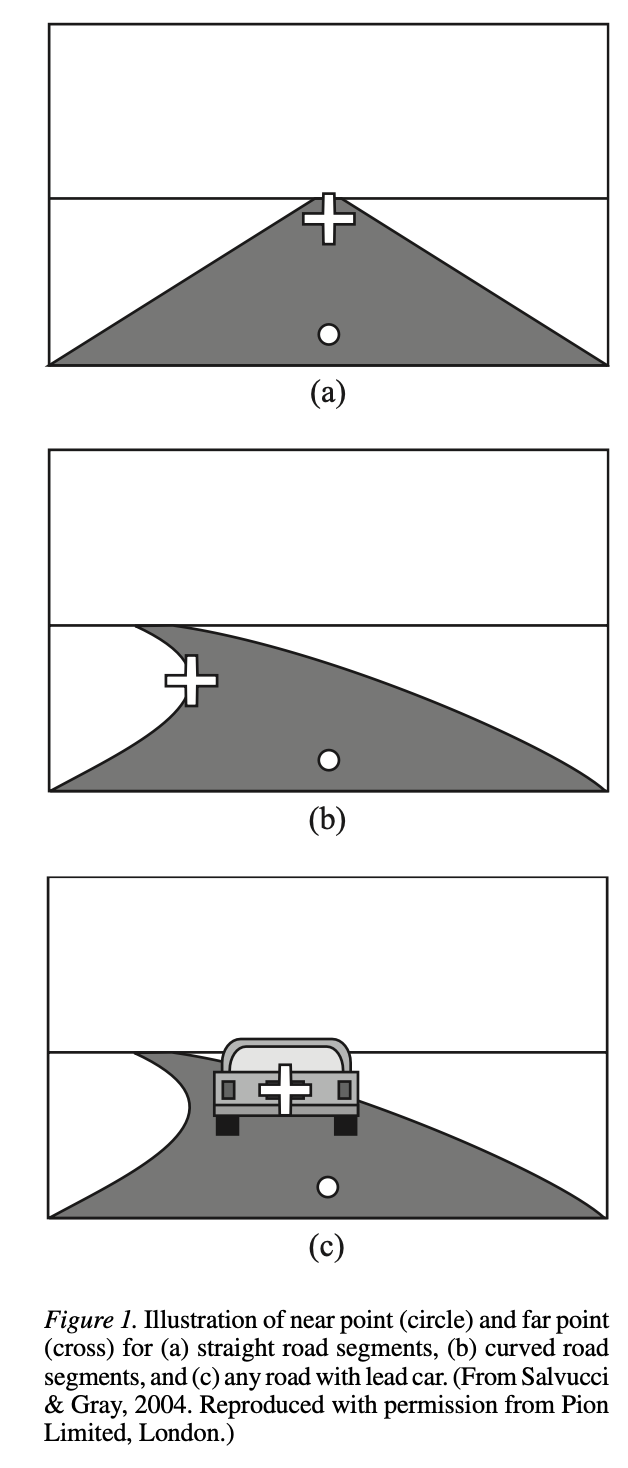

Between cognition and the vehicle lies the embodiment of the driver, namely the perceptual processes (visual, aural, vestibular, etc.) and motor processes (hands, feet) that provide the input from and output to the external world.

Not surprisingly, there can be parallelism in this integrated system – for instance, moving the hand while visually encoding the lead car – but there are also capacity constraints and/or bottlenecks that sometimes result in degraded performance.